This book fits neatly into the genre of ‘artist as monster’ if there is such a genre and I seem to have read several recently. It is a story that draws me but I am not quite sure why. Others that I can remember are Madame Matisse by Sophie Haydock, The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce, The Mischief Makers by Elizabeth Gifford and I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, with a patriarchal monster in the guise of a husband or father, often with a block in their creative work.

This book is no different. Set in Provence in the 1920s, Edouard Tartuffe or Tata, lives in an isolated cottage with his niece, Ettie, who cooks, cleans and prepares all the materials that he needs. She even chooses foods that will appeal to him that he will decide to paint, the slightly bruised peach, the pink radishes and the purple-tinged artichokes.

Joseph, a journalist in the making, manages to be invited to visit the cottage, staying as long as he will sit for a painting, Man with Orange. He is escaping his father’s expectations of him and the fact the he was a conscientious objector during the war. His brother resides in a hospital suffering with what we would now call PTSD but at the time attracted monstrous treatments.

The atmosphere of the novel is claustrophobic. The controlling nature of Tata, the pressing heat of the Provencal summer and the fact that no one is allowed to visit and Tata never leaves the house. What Tata is trying to capture is the light, something he can not control although he has removed all other variables.

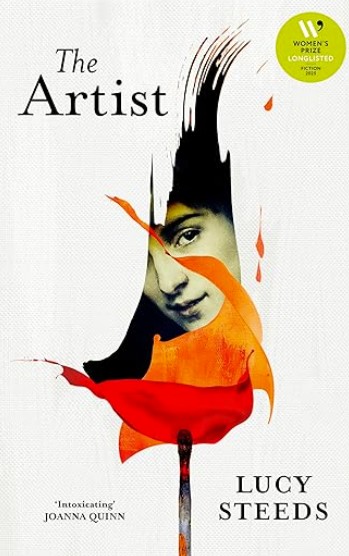

What is revealed is Ettie’s desire to be an artist and the many ways in which Tata refuses her the opportunity until she creates her own way to exact revenge. This was quite obvious as you move through the story but nevertheless is a fitting way to end.

Steeds writing is wonderful and describes the place beautifully. Told through the eyes of Joseph and Ettie but in third person, the story is revealed, allowing us to experience the emotions of both characters. Secrets are brought into the light including Ettie’s paintings.

‘You told me you didn’t know how to paint,’ Joseph says feebly. It is a small detail but he clutches onto it.

‘I told you Tata never taught me how to paint,’ says Ettie. ‘That’s not the same thing.’

‘Then how did you learn?’

‘By watching. By following. I have spent my life observing. It turns out it ws the perfect training.’

p209

And so we come to the heart of the book. The fact that looking is not the same as seeing and that light does not shine on everything equally.

I’d love to hear what you think